King William’s War and the Witchcraft Delusion (1689-1698)

In February 1690, when English settlers had no reason to suspect an attack, 110 French militiamen and 96 pro-French Iroquois attacked Schenectady, a village in the New York colony. The attackers crept silently into the settlement, guarded only by two snowmen at the gates, and took the settlers by complete surprise, slitting their throats and crushing the skulls of 60 men, women, and children. They took 27 as prisoners. William Cullen Bryant and Sydney Howard Gay. A Popular History of the United States, (New York: S. Scribner’s Sons, 1881)

Several Harvard Veterans played key roles in King William’s War (1689-1698). It was a long and often inhumane conflict that accomplished little other than loss of life among the populations of New England, New France, and the Native Americans who fought on both sides. Historians often characterize it as the first of four French and Indian wars, and when it was over, not a single boundary had changed in North America or in Europe.

The period stood in stark contrast to the twelve years of relative peace New England had experienced since the conclusion of King Philip’s War in 1678. Government transitions and witchcraft delusions magnified the contrast.

There was widespread support for the War effort among Harvard faculty, students, or alum. They mostly considered it to be a war of survival, fearing that the outcome would leave control of North America in the hands of the French, with the English being driven into the sea.

King James II’s personal adherence to the Catholic faith led to his overthrow as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Public Domain.

KING JAMES II

War clouds developed when James II ascended to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland in April 1685. At the beginning of his reign, the principle of divine right provided widespread support from his subjects, even though he was a Catholic ruling Anglican subjects.[1] His personal adherence to the Catholic faith soon sowed seeds of discord when he attempted to bring religious toleration to his kingdoms. When the Parliaments of England and Scotland voted against his religious tolerance measures, James unsuccessfully attempted to impose them by decree, further increasing dissent.[2]

In June 1688, descent turned to political crisis when James’s son and heir, James Francis Edward, was born. Dissenters and former supporters feared the creation of a Roman Catholic dynasty. To ensure Anglican succession, they favored his Anglican daughter Mary and her Protestant husband William III of Orange.

James II was oblivious to the extent of discord. When he prosecuted seven Anglican Bishops (including the Archbishop of Canterbury) for failing to read his Declaration of Indulgence (tolerance of Catholic worship) in their churches, opposition reached revolutionary levels. His opponents characterized the prosecutions as an assault on the Church of England. He lost the support of the courts when they acquitted the bishops. James’s political authority collapsed and anti-Catholic riots soon erupted in England and Scotland. Civil war seemed inevitable unless the opposition removed James II from the throne.[3]

THE CRISIS OF THE MASSACHUSETTS CHARTER

Meanwhile, Parliament had revoked the Massachusetts Charter in 1684. This was because the Massachusetts Bay colony, as a joint-stock colony (unlike a royal colony or proprietary colony) had been mostly self-governing for over sixty years. The colony had grown insubordinate in the eyes of Parliament and the crown, accusing the colony of thwarting English authority to legislate in New England. English grievances included assertions that Massachusetts was governing outside its charter (in New Hampshire and Maine), denying religious freedom (to anyone not a Puritan Congregationalist), coining its own money (the pine tree shilling) and deliberately violating the Navigation Acts (intended to manage trade within the English empire).[4]

Revocation of the charter broke the Puritan oligarchy that had ruled since establishment of the colony. Joseph Dudley (College, 1665), a hero of the Great Swamp Fight during King Philip’s War, took on the duties of acting Royal Governor in October 1685. Dudley, whose official title was President of the Council of New England, ruled with an appointed council and no representative legislature.[5]

After revocation of the original Massachusetts Bay Charter, Joseph Dudley, who had attended Harvard became President of the Council of New England and ruled with an appointed council and no representative legislature until Sir Edmund Andros arrived as Royal Governor from England and quickly made enemies out of most New Englanders. Dudley, left: Public Domain. Andros, right: Released to public domain, Rhode Island State House collection.

In late 1686, Sir Edmund Andros arrived as Royal Governor from England and quickly made enemies of most of most New Englanders. Landowners resented the taxes he imposed on their land and feared Andros might take their land titles. Merchants defied the Navigation Acts that Andros aggressively strove to enforce. Puritans hated the new policy of religious toleration. Finally, the lack of representative government angered most citizens (Andros limited town hall meetings to once a year and only to elect town councils).[6]

JOHN WISE

Harvard graduate Rev. John Wise (College, 1673) of Ipswich, became the voice of New England landowners. He was the first man in America ever known to articulate opposition to TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION. He strongly defended of the “civil and sacred liberties and privileges of his country,” and was “willing to sacrifice anything, but a good conscience, to secure and defend them.”[7]

Wise put the citizens' charges against Andros in writing and sent them to the government in England. He argued the practice or taxation without the consent of an elected general assembly infringed on the colonists' liberty “as freeborn English subjects of His Majesty.”[8]

When Governor Andros found out about the document, he responded by prosecuting Wise, along with five others from Ipswich, as criminals. The chief judge in the case was none other than Joseph Dudley. After Wise and the others made their defense, Dudley ruled that the laws of England did not follow its subjects “to the ends of the Earth.” After convicting Wise, Dudley told him he had no privileges left, except not to be sold as a slave.[9]

WILLIAM AND MARY and THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION

New England’s hatred of Andros (and Dudley) had grown nearly unanimous. When William and Mary took the throne of England in 1689, as part of the Glorious Revolution, the old guard Puritans imprisoned Andros. A Harvard graduate, Adam Winthrop (College 1668), played a key role in Andros’s surrender. He was the son of Adam Winthrop Sr. and grandson of John Winthrop, the first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony. Adam Winthrop was “Captain of one of the Boston companies of militia which assembled 18 April 1689 and a signer of the message demanding that Andros 'forthwith surrender and deliver up the government.'” His contemporaries lauded him for helping to end James II’s (and Andros’s) “attempt to crush self-government in New England.” [10] The citizens soon elected Winthrop to serve as Representative from Boston in the sessions of the General Court summoned meet from 1689 to 1692.

Harvard’s John Wise was also a representative at those sessions. After joining Winthrop in reorganizing the former Legislature, Wise sued Joseph Dudley under the new regime for “denying him the benefit of the habeas corpus act.” He reportedly recovered damages.[11]

After imprisoning Andros, the former ruling Puritan oligarchy attempted to get the original colonial charter reinstated but found tepid support for their cause among colonists not part of the former power elite. Without the support of the majority, the oligarchy, led by Increase Mather (College, 1656) found it impossible to revert to its former government structure. Instead, Mather settled for a royal colony with a governor appointed by the King. Under the new governmental structure, the citizenry threw off Puritan rule that had only allowed members of the Puritan (Congregational) Church to vote. Instead, the population gained greater political power and religious freedom. All property-owning men now had a vote and Protestants were free to worship as they pleased (Catholics, not so much). [12]

CHANGES AT HARVARD COLLEGE

There were changes at Harvard College during this time as well. Having lost power and influence in government, Puritan leaders realized the only way to maintain anything resembling their old power was by maintaining control of Harvard College. “Of all the institutions of the country,” historian Joshia Quincy wrote, “the College, next to the civil government, was that which they deemed the most important.” Since the college had been under their control since its founding, they believed they should still lead the College. Just as in government, the previously excluded citizens opposed them. Despite the odds against them, Increase and Cotton Mather led the charge to maintain control of the College by maintaining a “perpetual excitement” among the old power elite.[13] The Puritan elite was successful in maintaining control.

YOUNG DANIEL DENISON

The experience of Harvard student Daniel Denison (College, 1690) provides a glimpse of the experiences and hardships undertaken by Harvard’s veterans leading up to and during King William’s War. Denison had been but a boy when peace came to southern New England after King Philip’s War. Being from the village of Ipswich, he had experienced the horrid aftermath of war. He saw widows and maimed veterans throughout southern New England and experienced the devastated economy that after twelve years had not mounted a complete recovery.

When Denison enrolled at Harvard in 1886, he had a legitimate expectation for peace and recovery to continue. There were no rumors of war, and further progress seemed assured. Harvard had grown in the number of students and also in world-wide reputation since its founding fifty years prior in 1636. The General Court of Massachusetts had played an instrumental role in this growth with a series of Acts (1642, 1650, and 1657) improving the University’s corporate governance and powers. In 1661, the Court even answered the question, once and for all, of who “founded” Harvard. In an address to the Commissioners of Charles II, they named John Harvard as the “principal founder.”[14]

WAR COMES TO HARVARD

A year before Denison enrolled, Rev. Increase Mather took on the role of acting Harvard President “to take special care of the government of the College.” He served as acting president from that time until he became president in 1693, serving 16 years in leadership.[15]

As Denison’s years at Harvard progressed under Mather, rumors of war reached southern New England from the north, where the French and Iroquois Confederacy had been at odds for decades in the so-called Beaver Wars. In 1687, news of French raids into Iroquois territory (later upstate New York) reached southern New England. Even so, the struggles to the northwest had little impact on Harvard.[16]

The first signs of unraveling peace occurred in late 1688 when Louis XIV of France sent his forces into the Rhineland and the Low Countries (parts of Germany and the Netherlands today). King William III of England countered the French expansion by beginning the War of the League of Augsburg which lasted from 1689 to 1698 (known in North America as King William’s War).

In July 1689, the Beaver Wars took on a horrific character when the Iroquois League put French settlers on spits and roasted them at Lachine near Montreal.[17] The French in Canada, already at war against the Iroquois, wasted no time in engaging the English when war began in Europe. They mounted winter-time raids against English settlements that resulted in the death of some 200 English colonists.[18]

In February 1690, when English settlers had no reason to suspect an attack, 110 French militiamen and 96 pro-French Iroquois attacked Schenectady, a village in the New York colony. Seeking revenge for the Iroquois attack on Lachine, they crept silently into the settlement, guarded only by two snowmen at the gates. The attackers took the settlers by complete surprise, slitting their throats and crushing the skulls of 60 men, women, and children. They took 27 as prisoners.[19]

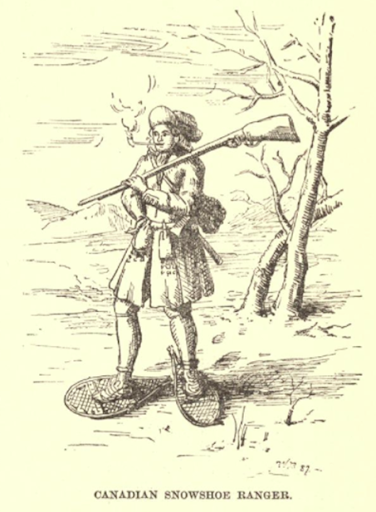

The French and their Native American allies used snowshoes as they descended from the North in the snows of winter to gain the element of surprise even during winter storms. As in the attack on Schenectady in the New York colony, they used snowshoes to move within striking distance, then removed the shoes and crept silently into the settlements for their attacks. Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England, commonly called King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars, (New York: C. Scribner’s sons, 1897). Public domain.

The attack on Schenectady was only the beginning. On 27 March 1690, the war came further south when a French war party attacked Salmon Falls, New Hampshire. When the attack was over, 34 settlers were dead. The French burned the settlement and took 54 prisoners. The prisoners didn’t fare well. By the time the war party reached Montreal, their captors had tortured most of them to death.[20]

Southern New Englanders reacted with alarm. They had to strike back, otherwise they feared the French would destroy the English settlements and drive them into the sea. Massachusetts Governor William Phips acted first when, on 11 May 11 1690, he led 700 militiamen and seven ships to take Port Royal on the Bay of Fundy. He laid siege to the port, and with little bloodshed, took it. His success boosted confidence and led Massachusetts to fund a late-summer expedition to Quebec with Phips once again commanding. This time, the mission objective would be twofold. First, destroy Quebec, the enemy’s power base. Second, plunder and bring back spoils of war. Massachusetts funded the campaign by selling bonds to be repaid with interest using the plunder taken from Quebec.[21]

Massachusetts Governor William Phips, on May 11, 1690, led 700 militiamen and seven ships to capture Port Royal on the Bay of Fundy, with little bloodshed. Encouraged by the success, Massachusetts funded a late-summer military expedition to Quebec by Phips, 2,000 militiamen, and an armada of ships. The mission was a failure with over 1,000 men lost. Public Domain.

PRIVATE DANIEL DENISON

When Daniel Denison graduated from Harvard College in July 1690, he rushed to Ipswich, Massachusetts to join his militia company as a private soldier.[22] He left with Phips’s expedition to Quebec in August. Six weeks later, packed in a troop-transport-ships and buffeted by the Atlantic Ocean for weeks, the air and sea spray grew cold and the ships darker and damper. The 18 transport ships and 4 warships were making slow progress up the Atlantic Coast with 2,000 militiamen toward the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. [23]

Things could be worse - sickness could catch hold or scant rations could run out. Like the other soldiers, Denison’s biggest fear was probably the weather. Storms along the Atlantic coast had claimed many a ship in the late summer and early fall. Why not an entire fleet on its way to capture Quebec?

As Denison considered the 63 officers chosen for the expedition, he would have thought of the two from Harvard. Captain Philip Nelson (College, 1654) was a veteran of King Philip’s War. He was a Justice of the Peace and a large landowner (said to own 3,000 acres). He was also captain of a military company. He survived the expedition to Quebec, but there is no record of his specific actions.

Harvard graduate, Captain Ephraim Savage (College, 1662) was also part of the expedition. He was captain of a militia company with members from Reading and elsewhere in Middlesex County.[24] A veteran of King Philip’s War, Savage was a trader in Boston. He became a member of an artillery company in 1674. In 1676, during King Philip’s War, the General Court ordered (then) Sergeant Savage to march up and take the command of a garrison in desperate need of provisions. Though his mission involved no combat, it was a success. In October 1677, the General Court made him an ensign. In 1683, he became captain of the militia company his father had once commanded.[25]

THE CHAPLAINS OF THE QUEBEC EXPEDITION

There were four Harvard graduates among the chaplain corps of the Quebec expedition. Grindall Rawson, John Wise, John Hale, and John Emerson. These four veterans upheld the Harvard tradition, begun during King Philips War, of providing wartime chaplains to the militia.

Grindall Rawson (College, 1678) was part of the expedition, though information on his specific actions is not available. John Wise (College, 1673), discussed above, discharged “his sacred office” during the expedition with heroic spirit along with “martial skill and wisdom.” He so distinguished himself that the legislature later granted 300-acres to his children and legal heirs in 1736.[26]

In 1690, when John Hale (College, 1673) wanted to become a chaplain in Phips’s expedition, his congregation objected. Hale, however, insisted on joining the expedition because so many of his congregants were among the militiamen who would set sail for Quebec. The Massachusetts Legislature agreed he would best serve the colony by looking out for the moral and religious welfare of the militiamen and sailors on the expedition. He served from 4 June to 20 November, all the way to Quebec and back. Knowing French, he also acted as interpreter. His service during King William’s War was meritorious. His heirs received a legislative grant of 300-acres on 31 December 1735.[27]

Another Harvard graduate, John Emerson (College, 1675) was part of Quebec expedition. He had previously served during King William’s War. He served “faithfully” as chaplain to the forces at Berwick from September 1689 to November 1689, as hostilities were intensifying in that region. It wasn’t the first time, however, Emerson had experienced danger in that location.[28]

He was the “Preacher at Berwick” five years prior, in 1684, as tensions between colonists and the Penacook tribe were at a boiling point. The tensions had been high since before Prince Philip’s War (1676-78). The tribe was angry with the commander at the Cochecho garrison, Major Richard Walderne, who had a decade earlier lured members of the tribe into a “sham battle.”[29]

Walderne had convinced Penacook and Massachusetts nation warriors to camp close to settlement for “war games” set to begin the next day. It was a trap. During the night, four militia companies surrounded the camp and captured 200 Massachusetts nation warriors. After marching the warriors to Boston, authorities hung some of them while selling others into slavery.[30]

As the years progressed, Chief Kancamagus of the Penacook took over leadership of his nation. He “bitterly resented the injustices meted out by English settlers to his people” and resented restrictions on Penacook travel “in the woods east of the Merrimack without written permission from Major Walderne.” He decried the great injustice of Penacook land taken for paltry payments like a “peck of corn annually for each family.”[31] Kancamagus wanted revenge, but had to overcome a major obstacle. An “eight-foot palisade of large logs set upright in the ground” surrounded the settlement of Cochecho, which its fortified blockhouse “impenetrable to bullets.”[32]

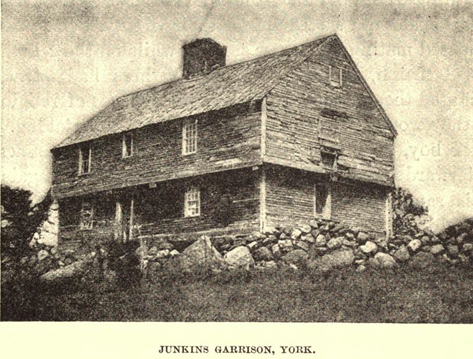

The stronghold of Cochecho looked much like the one in York. Surrounded by an eight-foot palisade of large logs set upright in the ground, the fortified blockhouse (like the one pictured) had foot-thick logs impenetrable to bullets. Defenders removed loose boards where the second story overhung the first to pour boiling water on attackers and extinguish attempts to burn the blockhouse down. Public Domain.

On 27 June 1684, while Emerson was visiting Cochecho, Governor Bradford sent a letter to Major Walderne, warning of a nearby gathering of Penacook “with the design of mischief.” That evening, the letter had yet to reach Walderne, who had no reason to suspect an attack was eminent. Even so, he believed it unwise for Emerson to travel in the evening, given the current agitation among the Penacook. He strongly urged Emerson to stay with him until the morning, when it would be safer to travel. For whatever reason, Emerson declined, and went on his way.[33]

That night, several Penacook women sought shelter within the Cochecho garrison. Because this was a common practice in peacetime and the governor’s warning had not arrived, the women “were shown how to open the doors and gates in case they wanted to leave in the night.”[34]

Walderne had no reason to suspect “mischief,” so he posted no watch. During the dark hours of the morning, the Penacook women “quietly opened the gates to several hundred Penacooks.” They rushed into the garrison, overpowered the 74-year-old Walderne, and tied him to a chair. “The furious Penacooks” each slashed the old man across the chest with his own sword, yelling “I cross out my account!” Had Emerson been in the home, he would have probably suffered a similar fate. In the words of a contemporary writer, Emerson “received a remarkable Deliverance” from certain death by departing earlier that evening.[35]

The attackers killed 23 colonists that night and took 29 more prisoners. The Penacook burned the garrison houses and a mill to the ground. When the survivors counted the dead, Walderne was among them.[36]

While Emerson was a chaplain and minister, he was also a teacher at various places, including Newbury, Gloucester, and Charlestown, Massachusetts. He taught Greek, Latin, writing, mathematics, and reading. By the time King William’s War erupted, he was becoming known as the “Famous Master Emerson.” During his career, he prepared many of his pupils (like Thomas Symmes, (College, 1698) to enter Harvard.[37]

THE ASSAULT ON QUEBEC

With 1,200 militiamen pinned down in the woods outside of Quebec by French forces, William Phips bombarded Quebec with his four warships. Phips failed to adequately resupplied his men on shore so they could continue their attack. When the militia did not reach Quebec and the bombardment did not bring about a surrender, Phips re-boarded the militia and sailed for Boston. Public Domain.

The four chaplains, along with Captain Nelson, Captain Savage, and Private Daniel Denison, knew battle was approaching when the fleet entered the St. Lawrence River. The ships, however, had no pilots on board with knowledge of the St. Lawrence River. As a result, they were extremely slow in their ascent of the river. The French, on the other hand, had been given early warning and plenty of time to prepare their defense.[38]

When the fleet arrived in Quebec in October, a cool Canadian wind was blowing. Phips demanded surrender, but the garrison refused. Phips responded by putting 1,200 militia ashore to prepare for an assault on the citadel.[39] Captain Ephraim Savage’s father, Regimental Commander, Major Thomas Savage, was the first Field-Officer ashore. 600 Frenchmen immediately ambushed his force.[40] Ephraim Savage, in a separate ship, ran aground near where his father’s regiment was fighting. Two hundred more French soldiers attacked his ship from the shore. The attack was unsuccessful and Captain Savage was soon ashore with his sixty men “running very briskly” into the French lines.[41] The Savages, father and son, “beat up their Ambuscade [the French ambush],” and followed them a great way, wading “up to their middle” in the cold swamps. At sunset, the militia encamped, having “spent the greatest part of [their] Ammunition” in the day’s fighting.[42]

Meanwhile, Phips bombarded Quebec with his four warships, but never adequately resupplied the men he had put ashore. With his men bogged down on land and the bombardment ineffective in bringing about a surrender, Phips re-boarded the militia on to the ships three days after landing them.[43]

Back on the ships, French prisoners revealed that if the militia had “come but four days sooner,” there had been less than 600 men to defend Quebec. The delay in navigating the St. Lawrence River had been the key factor in not taking the city. By the time the expedition reached Quebec, the French had 3,000 defenders, with eight hundred more in the surrounding swamps and woods.[44]

Before departing for Boston, a prisoner exchange occurred. The British Prisoners, who had been with the French before the New Englanders arrived, informed Phips that if the militia had gone any further, the superior numbers of the French in the woods and in the city would certainly have destroyed them.[45] These prisoners revealed another truth. Had the Phips set up a siege, it is probable they would have forced the French to surrender the city. They did not have the food to sustain a force of 3,000 mouths for any longer than a week.[46]

THE DISASTROUS RETURN HOME

In any war, commanders must plan for the enemy, the weather, sanitation, and many other things. While sailing back to Boston, storms caught Phips’s ships in the open, sinking several and killing many soldiers and sailors. Others, victims of the cramped and unsanitary transport ships, caught smallpox and died. According to one historian, “Over 1,000 men, nearly half of Phips’s army, perished before the armada reentered Boston harbor.”[47] Among the dead was young Daniel Denison, dying only a few months after graduating from Harvard. Whether he fell “before the grim citadel of Quebec,” drowned when his ship sank in the storm, or died of smallpox, we have no record.[48]

THE YORK MASSACRE

Some Harvard casualties during King William’s War were not the result of militia duty. For example, Rev. Shubael Dummer (College, 1656), was the minister of Old York, Maine in 1692 when French and Indian forces under the leadership of Chief Madockawando and Father Louis-Perry Thury raided the frontier town.[49] Dummer had remained in York against his better judgement. He had every reason to leave when war clouds “grew thick and black” and the war, at any moment, might “break upon” York. He chose, instead, “with a paternal affection” to remain with those who had nowhere else to go, feeling responsible for the many who had been “converted and edified by his Ministry.”[50]

On the morning of 25 January 1692, a “Body of Indians and French Canadians over one hundred strong,” arrived on snow-shoes and attacked the town. They soon overran the scattered houses of York.[51] It was a Sunday morning and Dummer was preparing to take his Horse on “a Journey in the Service of God, when the [enemies] that were making their Depredations upon the Sheep of York seized upon this their Shepherd [Dummer] and they shot him.” His neighbors found Dummer face down and dead, “near his own front door.” At least 48 died in the massacre that day (some accounts put the death toll as high as 100). The French and their Native American allies took 80 captives.[52]

Harvard graduate and Veteran, John Wise, wrote about the Witch Trials. It was a time when “we walked in the clouds, and could not see our way.” He played a role in ending the trials. Years after their occurrence, he wrote, “The wildest storm … that ever raged in the moral world … [sank] back to its peaceful bed. There are few, if any, other instances in history, of a revolution of opinion so sudden, so rapid, and so complete.” Public Domain.

THE WITCH TRIALS

As the horrors of King William’s War raged on, many English settlers became enmeshed in supernatural “delusion” and a fear of witchcraft. Harvard’s veterans were not exempt. Supernatural delusion ensnared Captain Philip Nelson when he pretended to cure a deaf and dumb boy by imitating Jesus Christ. In doing so, he gave the command “Ephphatha,” an Aramaic word meaning, “be opened.” It was the same word uttered by Christ when he healed a deaf and dumb man as described in the Gospel of Mark.[53] According to Sibley’s Biographical Sketches of Harvard Graduates, the ministers of the neighboring churches brought the boy before them, to see if he could speak. They questioned him, but church records say he stood there like the “deaf and dumb boy as he was.”[54]

The supernatural delusions of the time generated a fear of witchcraft that led to trials and executions of many innocent people. This witchcraft mania overcame a few Harvard-educated military chaplains. Chaplain John Emerson, for example, was most likely the Emerson who extracted a confession from at least one accused witch, the Goodwife Tyler. In her recantation of the confession years later, she said that she was so mentally abused by Emerson that she became “terrified in her mind.”[55] He insisted that she was “most certainly” a witch and attempted to convince her that “she saw the devil before her eyes.” He attempted to beat the devil away from her with his hands. Her anguish was so severe that she asked to be placed in a dungeon rather than endure any more abuse. Mentally abused and exhausted, she confessed to being a witch to escape anymore of Emerson’s torment.[56]

Another chaplain, John Hale, was present at several of the witch trials and knew many of those that suffered. He saw four of his parishioners, accused and condemned. He became one of the first people (with the power to persuade) to suspect the accusers. It is not surprising that his change of heart occurred when the accusers identified his wife as a witch. Knowing first hand, her “innocence and piety,” he “stood forth between her and the storm he had helped to raise.”[57]

Hale defended his wife until the community became convinced that the accusers had brought false charges and “had perjured themselves.” In doing so, he destroyed the power of their lie and, along with it, “the awful delusion” that had corrupted the community. “One of the most tremendous tragedies in the history of real life” ended because of Hale’s stand.[58]

Hale later wrote about “the errors and mistakes,” of 1692. He mourned the “darkness of that day, the tortures and lamentations of the afflicted.” It was a time, he wrote, when “we walked in the clouds, and could not see our way.” In his words, “The wildest storm, perhaps, that ever raged in the moral world, became a calm; the tide that had threatened to overwhelm everything in its fury, sunk back to its peaceful bed. There are few, if any, other instances in history, of a revolution of opinion so sudden, so rapid, and so complete.”[59]

The war continued as a series of raids back and forth between New England and New France, with its last battle occurring at Damariscotta, Maine on 9 September 1697 and officially ending on 30 October 1697, with the Treaty of Ryswick. The terms of the treaty restored all conquered territories. The lives lost had been for nothing and the disputed areas between New England and New France remained disputed. Those unsettled boundaries, combined “with other differences of still greater importance, led England to declare war against France and Spain just a few years later - May 1702.”[60]

In reality, the war still raged in North American. It wound to its end only after the signing of two agreements. On 7 January 1699, the Abenaki Nation and the Massachusetts colony signed a peace treaty at Casco Bay, Maine. Then, in 1701, the Five Iroquois Nations and 35 other native nations signed a peace agreement with New France, known as the Great Peace of Montreal.

During King William’s War, the French and their Native American allies made some sixty attacks on New England settlements and slew at least 650 colonists in battle, massacre, or captivity. Areas of New York saw the population decrease by 25% as settlers fled the constant threat of the French and their allies. The portions of the Iroquois Nation allied with the English lost at least 600 from battle and disease (some estimates put the number as high as 1,300). About 300 French died in the war along with 300 of their Native American allies.[61]

HARVARD PARTICIPATION IN THE WAR

Given the length of the war, and the number of citizens serving under arms, Harvard participation of King William’s War was not robust. Even so, there is no evidence of vocal opposition or protest by Harvard students, faculty or alumni.

In policy and governance, Harvard graduates played key roles. Joseph Dudley (College, 1665) took on the duties of acting Royal Governor in October 1685, and ruled tyrannically as President of the Council of New England with an appointed council and no representative legislature. After Sir Edmund Andros arrived as Royal Governor, Dudley continued to make enemies by supporting Andros and even prosecuting his fellow Harvard graduates.

Rev. John Wise (College, 1673) was the first in America to oppose the idea TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION. He put charges against Andros in writing and sent them to the government in England. After Dudley convicted him of sedition, Wise joined Adam Winthrop (College 1668) in securing Andros’s surrender. Wise and Winthrop served as representatives in the sessions of the General Court. After imprisoning Andros, the former ruling Puritan oligarchy under the leadership of Increase Mather (College, 1656) attempted to get the original colonial charter reinstated but ultimately secured a charter with greater political power and religious freedom.

The horrors of war created an internal turmoil in many New Englanders, causing them to succumb to the witchcraft delusion. John Hale (College, 1673), was the first to become suspicious of the accusers, convincing the community the accusers had brought false charges and “had perjured themselves.” In doing so, he destroyed the power of the delusion and ended the persecution of innocents.

[1] Tim Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 1685–1720 (Penguin Books: London, 2006), 6-7.

[2] Tim Harris, Stephen Taylor, eds, The Final Crisis of the Stuart Monarchy (Boydell & Brewer: Suffolk, 2015), 144-159.

[3] Harris, Revolution: The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy, 264-68.

[4] Viola Florence Barnes, The Dominion of New England: A Study in British Colonial Policy (Yale University Press: New Haven, 1923), 6, 10-18.

[5] Barnes, The Dominion of New England, 47-48.

[6] Barnes, The Dominion of New England, 46.

[7] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge University, Vol. 2, (Charles William Sever: Cambridge, 1881) 428-429.

[8] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 428-30.

[9] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 431.

[10] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 427-29

[11] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 432.

[12] Josiah Quincy, The History of Harvard University (John Owen: Cambridge, 1840), 65-67.

[13] Quincy, The History of Harvard University, 65-67.

[14] Quincy, The History of Harvard University, 39.

[15] Quincy, The History of Harvard University, 38.

[16] John Grenier, “King Williams War: New England’s Mournful Decade,” History Net, https://www.historynet.com/king-williams-war-new-englands-mournful-decade.htm, accessed 17 Aug 2021.

[17] Grenier, “King Williams War: New England’s Mournful Decade.”

[18] Charles Augustus Goodrich, A History of the United States of America (D.F. Robinson & Co: Hartford, 1831), 81.

[19] Grenier, “King Williams War: New England’s Mournful Decade.”

[20] Grenier, “King Williams War: New England’s Mournful Decade.”

[21] Grenier, “King Williams War: New England’s Mournful Decade.”

[22] Samuel Eliot Morison “Harvard in the Colonial Wars, 1675-1748,” The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine, Vol. XXVI, September, 1917, 562-63

[23] Some accounts say there were thirty-two ships. Letter from Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders, Under the Command of Sir William Phips, Against the French at Canada, as licensed April 13. 1691 (Thomas Jones: London, 1691).

[24] Lawrence Park, Major Thomas Savage of Boston and His Descendants (David Clapp & Son: Boston, 1914), 11-14.

[25] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 128.

[26] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 432-33.

[27] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge University, Vol. 1, (Charles William Sever: Cambridge, 1873) 513.

[28] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 2, 472.

[29] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website, https://www.dover.nh.gov/government/city-operations/library/history/the-cochecho-massacre.html, accessed 17 Aug 2021.

[30] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[31] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[32] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[33] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[34] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[35] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website, Sibley, 472.

[36] “The Cochecho Massacre,” Dover Public Library Website.

[37] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472.

[38] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[39] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[40] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[41] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[42] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[43] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[44] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[45] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[46] Thomas Savage to Perez Savage, 2 Feb 1691, An Account of the Late Action of the New-Englanders.

[47] https://www.historynet.com/king-williams-war-new-englands-mournful-decade.htm

[48] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472-473.

[49] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472-473.

[50] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472-473.

[51] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 473.

[52] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 473.

[53] Gospel of Mark, 7:34, https://www.biblestudytools.com/dictionary/ephphatha/

[54] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 386; https://www.geni.com/people/Capt-Phillip-Nelson/6000000011873250131.

[55] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472.

[56] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 472.

[57] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 514.

[58] Sibley, Biographical Sketches, Vol. 1, 514.

[59] 167-167, 514.1-516.1 A Modest Enquiry into the Nature of Witchcraft, and How Persons Guilty of that Crime may be Convicted: And the means used for their Discovery Discussed, both Negatively and Affirmatively, according to Scripture and Experience. Boston B. Green & J. Allen: Boston, 1702).

[60] Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, 86.

[61] Howard H. Peckham, The Colonial Wars, 1689-1762 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964), 53.