HARVARD AND QUEEN ANNE’S WAR (1702-1713)

by Major General (USAF, Retired) Samuel C. Mahaney (NSF ’08),

Harvard Veteran Alumni Organization Historian

June 2022

INTRODUCTION

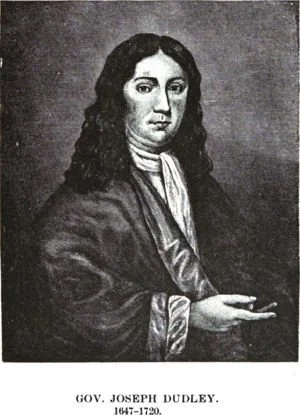

Joseph Dudley (College, 1665) and John Leverett (College, 1680) were among the very best of seventeenth century Harvard graduates. They each provided decisive leadership for the militia, the colony, and for Harvard College when most other leaders of the time failed to grasp what they must do to confront the changing world facing them at the dawn of the eighteenth century. Together, Dudley and Leverett focused on strengthening the colonies’ provincial security, jurisprudence, and liberal education.

During his time as the Provincial Governor, Dudley took great interest in the success of Harvard College. Leverett divided his immense energy between being a jurist, international negotiator, and soldier, before becoming Harvard’s seventh President and the first military veteran to hold that post. As Harvard’s President, Leverett continued to support Dudley as each strove to defend the New England frontier from the French and their Native American allies during Queen Anne’s War.

While this story contains much of Dudley and Leverett’s contributions, it also describes the exploits of other Harvard graduates who took up arms on behalf of their fellow citizens and helped shape the future of New England and America early in the 18th century.

As Governor of Massachusetts, Joseph Dudley took great interest in the progress of Harvard College.

JOSEPH DUDLEY

It was 1702, and New England groaned in anticipation of a tyrant landing upon its shore. The tyrant’s name was Joseph Dudley, a Harvard graduate (College, 1665). His career had peaked in the eyes of most New Englanders when he was a hero of the Great Swamp Fight of December 1675 during King Philip’s War.[1] A decade after that war, Dudley’s star fell so far that his fellow New Englanders jailed him and sent him back to England.

How had Dudley fallen so far? The answer lies in the sweeping governmental changes of the late 17th century. The Massachusetts Bay Colony had been mostly self-governing for over sixty years, but in 1684 Parliament revoked the Massachusetts Charter because the colony had long thwarted English authority to legislate in New England. Under the new charter, the Crown appointed Dudley as President of the Council of New England, and then Chief Magistrate in 1686 under Sir Edmund Andros, the Royal Governor sent from England. The two men quickly made enemies. Landowners resented the taxes imposed on their land and feared Andros might take their land titles. Merchants defied the Navigation Acts that Andros aggressively strove to enforce. Puritans hated the new policy of religious toleration. Finally, the lack of representative government created anger and resentment.[2]

Dudley, in the position of Chief Magistrate, offered his fellow New Englanders no recourse against Andros. Instead, he prosecuted those who failed to obey Andros’s dictates. His prosecutions included fellow Harvard graduates like Rev. John Wise (College, 1673) of Ipswich. Wise was the first man in America ever known to articulate opposition to taxation without representation, and sent charges against Andros to the government in England.

When Dudley found out, he prosecuted and convicted Wise of sedition in New England’s highest court. Dudley did not believe Wise could interpret English law to allow him to protest without the threat of prosecution for sedition. Dudley, therefore, established a judicial doctrine that the laws of England did not follow its subjects “to the ends of the Earth,” or to New England for that matter. After convicting Wise, Dudley told him he had no privileges left under English law, except not to be sold as a slave.[3]

The favor Dudley enjoyed from 1685 to 1689 changed for the worst when William III of Orange (third in line to the English throne) and his wife Mary (first in line) took the throne from Mary’s father, James II in 1689. They became joint sovereigns of England, Scotland, and Ireland. As a result, Andros and Dudley no longer had legitimate mandates from the Crown.

Several Harvard graduates, including Wise, Adam Winthrop (College 1668), and Increase Mather (College, 1656), played a role in forcing Andros and Dudley to surrender their authority. They jailed the two men and then sent them away to England.[4]

Despite being thrown out of New England, Dudley returned three years later, on June 11, 1702, as Governor of the Province of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. After the way he and Andros had behaved during their rule, New Englanders feared the return of totalitarianism. Many of those involved in jailing Dudley worried he would seek retribution and began “to shake and tremble at the news of Col. Dudley’s coming.”[5] Optimists, on the other hand, pointed out that things could be worse. England, they argued, might instead have sent an aristocratic idiot. At least Dudley was a native and had a genuine talent for leadership and governance.[6]

The optimists were correct. The first thing Dudley did after landing was provide a general amnesty to those involved in jailing him. According to historian Michael G. Laramie, most saw his willingness to let bygones be bygones “… as a mark of leadership and a sincere desire to unify the colony.” [7]

QUEEN ANNE’S WAR BEGINS - 1702

Whatever Dudley’s plans for the province, the War of Spanish Succession in Europe soon overshadowed them. The war, known as Queen Anne’s War in North America, pitted France and Spain against England, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Dutch. The primary issues were who would become king of Spain and whether the son of the deposed English King James II was the rightful ruler of England instead of William and Mary.[8]

Because of war in Europe, the French and English were once again at war again in North America, causing Dudley had to take proactive steps to protect New England. He sent four hundred militia troops to the Maine frontier, placed a company of mounted militia on the coastal King’s Road, and gathered another six hundred militia in Boston. He also asked Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York for at least another three hundred men, but those colonies were of little help.[9]

Dudley took charge of the frontier, emptying garrisons in Maine of women and children, and ordering those remaining on the frontier to gain the protection of their garrison houses at night. Small groups of French and native raiders still struck up and down the frontier, but Dudley had done all he could up to that point of the war to protect the province.[10]

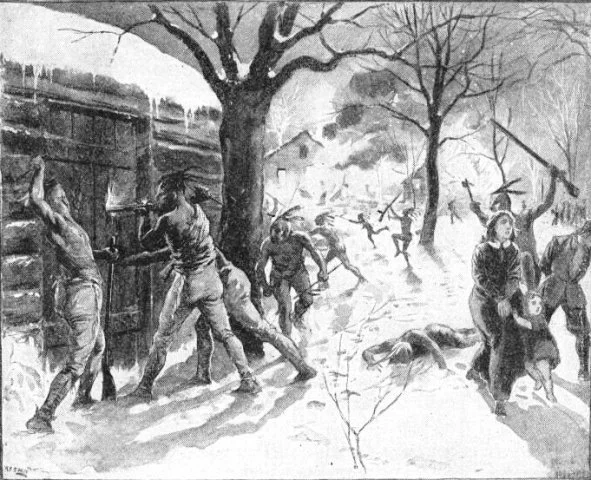

In 1704, over 280 French and Native Attackers burned most of Deerfield Mass, killed 56, and captured 109.

THE DEERFIELD MASSACRE – 1704

In late May 1703, Dudley notified Harvard graduate Rev. John Williams (College, 1683), the minister at Deerfield, Massachusetts, to expect an attack by the French. Besides his warnings, Dudley sent twenty militiamen to Deerfield.

Williams was no stranger to attacks on the community, having endured several during King William’s War (1688-1697). He preached a common theme of Harvard trained ministers - vigilance and readiness. But as summer and autumn passed with no attack, vigilance slackened and preparedness faded among the villagers and the soldiers. By the time winter snow blanketed the ground, preparedness was nonexistent. The villagers doubted the French would brave a 300-mile march in the dead of winter to attack, and then trek back in the same winter cold.

The villagers were wrong.

The French made the trek across the Green Mountains and followed the Connecticut River to Deerfield. 48 Frenchmen were among the attackers, several of whom had over 20 years’ experience in frontier warfare. About 240 Native Americans were also in the party, including Abenaki, Mohawk, Wyandot-Huron, Pocumtuck, and Pennacook warriors. Some among the native population had yet to avenge violence by white settlers from years earlier.[11]

In the darkness of the early morning on February 29, 1704, the sound of a sentry’s musket broke the frigid air. Like many in the village, John Williams did not hear the shot, but heard the attackers shatter the windows of his home. Williams yelled the alarm to two militiamen sleeping upstairs and hid in his bedroom with his pistol at the ready. When one attacker broke through the bedroom door, Williams pointed his pistol and pulled the trigger. The gun clicked, but didn’t fire. The attackers subdued him. Meanwhile, the upstairs militiamen jumped from a second-story window to escape. The attackers rounded up the Williams family and, at the front door, engaged in a gruesome decision-making process. They decided the two younger children (aged six years and six months) would never survive the march to Canada. An enslaved woman named Parthena recognized what the attackers were contemplating and stepped between them and the children. The attackers had no mercy. They tomahawked Parthena and the two children to death.[12]

After the attack was underway, Militias from surrounding towns saw smoke rising from Deerfield and organized to drive away the attackers. They arrived at Deerfield and skirmished with the attackers before tracking the fleeing raiders a few miles from the town. After breaking off the skirmish, the militia waited for reinforcements to arrive. After a council, they decided not to pursue the French because the risk of an ambush in the wilds was too high.[13]

Later, Dudley was not happy with the decision of the militia leaders and, in not so eloquent words, alleged a lack of courage and honor. “I am oppressed,” he said, “with the remembrance of my sleepy neighbors at Deerfield, and all that came to their assistance, could not make out snow-shoes enough to follow a drunk, loaden [sic], tired enemy of whom they might have been masters to their honor.”[14]

One hundred-nine English captives began the 300-mile march into Canada, ill-prepared for the winter cold. Among the captives were two future Harvard Graduates: John Williams’s eleven-year-old son Stephen (College, 1713) and his five-year-old son Warham (College, 1719).[15] Williams and his two sons witnessed the savagery and cruelty of the raiders as they murdered his wife, Eunice. Having given birth just six weeks earlier, she was one of the first to be murdered, her body left amidst blood covered snow. The Deerfield community recovered her body soon after her murder and buried her in the Deerfield cemetery.[16]

Like Eunice, many other captives either succumbed to the elements or were murdered. John Williams noted the murders were not “random or wanton.” The raiders only killed those who delayed the progress of the march. He bitterly lamented, however, that the French would not have needed to murder the weak captives had they not taken them to begin with. Only 89 of the 109 captives survived the ordeal.[17]

Williams showed leadership throughout the march into Canada. On Sunday March 5th, five days after the raid, he conducted a worship service on a riverbank near what is now Rockingham, Vermont. The river is called the Williams River in his honor.[18]

BENJAMIN CHURCH – 1704

The governors of the northern colonies demanded action against the French colonies in retaliation for Deerfield. Dudley had a plan to end the current war and prevent future conflicts with the French in North America. He wrote to the Crown that “the destruction of Quebec and Port Royal [would] put all the Naval stores into Her Majesty’s hands, and forever make an end of an Indian War.” While awaiting a response from the Crown, he fortified the frontier between Deerfield and Wells with over 2,000 militiamen, and increased the bounty for native scalps from £40 to £100.[19]

The governors were not the only ones seeking retaliation. In March 1704, Benjamin Church, the province’s most experienced wilderness and frontier campaigner, came out of retirement when he heard of the raid on Deerfield. At age sixty-five, Church volunteered to lead a retaliatory strike against the French. Dudley had served with Church during King Philip’s War at the Great Swamp fight, and though he worried Church’s age might be a detriment, he put his trust in Church’s military knowledge and experience, which was more than all other potential commanders combined.[20]

Church took three warships, twenty transport ships, and 1,900 men from Boston to Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia). He raided four Acadian villages, but did not attack Port Royal because his instructions from a cautious Dudley forbade him to attack what might to be a well-defended garrison.[21]

Though he didn’t achieve major strategic goals (such as defeating Port Royal), Church used the force given him and accomplished a series of tactical wins. He claimed nearly a hundred prisoners and delivered a blow to the towns of Acadia that were like what the French and their allies had inflicted on New England. With Church’s tactical wins, Dudley counted some operational and strategic victories as well. First, Church’s exploits foiled a planned French attack against Newcastle. Second, the addition of Church’s prisoners created more leverage for Dudley to get English prisoners, back from the French.

When Church failed to conquer French territory, however, the naysayers (led by Cotton Mather) denied he had won any victory. Instead, they said that Dudley had aided the enemy.[22] Dudley’s strategy of achieving small victories until getting robust help from England to attack strongholds like Port Royal and Quebec was lost on Mather and his near-sighted supporters.

OTHER HARVARD VETERANS – 1704, 1705

Other Harvard graduates beside Dudley were active in 1704. Future Harvard President John Leverett (College, 1680) already had more than his share of responsibility and workload as justice of the Superior Court (1702-1708), and Judge of Probate Court for Middlesex County (1702-1708). Even so, he volunteered to do his part as an Indian commissioner from Massachusetts. He tried but could not convince the Iroquois to side with the British against the French.

Another Harvard graduate, Rev. Samuel Moody (College, 1689), joined the fight against the French. The son of Joshua Moody (College, 1653) of Swamp fight fame, Samuel was no stranger to the concept of service before self. He was captain of the garrison at St. John, Newfoundland from 1704 to 1705, then commanded Fort Casco near Portland, Maine, for the rest of the war.[23]

While at Fort Casco, support from the French for the Native Americans in the region flagged. “Left to shift for themselves, no time was lost in suing for peace… Captain Moody forwarded their request to Governor Dudley, who agreed to hold [treaty talks] at Portsmouth.”[24]

In 1705, another Harvard graduate, the son of Gov. Dudley, William Dudley (College, 1704) set aside progress on his master’s degree at Harvard to provide service to New England. As a nineteen-year-old, he went to Montreal with two other envoys attempting to secure the release of John Williams, among others, as part of a prisoner exchange. Joseph Dudley had other reasons for sending his son, including a desire to give him international negotiating experience and add esteem to the Dudley name.[25]

After many proposals and counter-proposals, William and other envoys returned to Boston with one of Williams’s sons in hand. William Dudley and Samuel Vetch then returned to Quebec in July 1705. By the autumn, the two sides had exchanged hundreds of prisoners, including Rev. Williams and his remaining son after more than a year in captivity. Williams would eventually serve in the militia with a commission as chaplain of the unsuccessful expedition against Quebec in 1711.

The Dudley-Vetch mission was not without controversy. New Englanders accused Governor Dudley of illegal trade with the French in Canada. Nothing came of the accusations against the governor, but William Dudley’s co-negotiator, Vetch, was convicted of trading with the enemy. Young Dudley, however, was not accused of any wrongdoing, having not been party to any of the older men’s schemes.[26]

PORT ROYAL – 1707

Negotiations for prisoner exchanges offered hope of a lasting peace. As a result, in 1705, nothing but scattered incidents occurred on the New England frontier. There were no raids by the French on the British or vice versa. As 1706 progressed, the English frontier slipped into a false sense of security and a lack of vigilance. As preparedness lapsed, the French and their allies launched July raids against Dunstable, Reading, Chelmsford, Sudbury, Hatfield, Brookfield, and Groton.[27]

With a sagging reputation, Dudley wanted to respond to the raids with a bold stroke and became impatient waiting for England to provide a robust naval and ground force. He took matter into his own hands by constructing a plan to defeat Port Royal, “the great pest and trouble of all Navigation and Trade … on the coast of North America.” He took the plan to the provincial legislature, and being as impatient as Dudley, they approved.[28]

Many Harvard graduates took place in the springtime 1707 expedition against Port Royal. Lt Col Francis Wainwright (College, 1668), a veteran of King William’s War, was second in command of the expedition. Wainwright’s family had a strong tradition of military service with his father (Francis Wainwright) having taken up the rifle in the Pequot War (1636-1638) as a 13 years-old boy.[29]

John Leverett, future President of Harvard, joined the expedition as a lieutenant in the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, the oldest chartered military organization in North America (March 1638) and still the third oldest chartered military organization in the world. Leverett commanded a company of volunteers, while also a justice of the Superior Court, Judge of Probate Court for Middlesex County, and a member of the Provincial Council (1706-1708).[30]

The expedition against Port Royal had a promising beginning. The Colonial militia, under the command of Col John Marsh, had pinned the French inside their fort and, by most accounts, could have maintained a siege leading to the surrender of the fort. But Marsh didn’t possess the resolve required of a military commander and failed to seize the initiative. When the militia forces returned to Boston relatively unscathed, the legislature and its citizens ridiculed the militiamen and their leaders for returning without attempting a siege of Port Royal.

Harvard graduate Francis Wainwright, feeling the sting of rebuke and disliking the damage to the Wainwright family reputation, urged Dudley to launch a second attack. With so many able-bodied soldiers still under enlistment, the General Court appointed Harvard graduate John Leverett as commissioner (along with two others) with the authority to overrule Colonel Marsh should his plans not be adequate to capture the port.

As commissioner, Leverett found himself surrounded with Harvard graduates, including Wainwright as second in command. Capt Ephraim Savage (College, 1662), a veteran of King Philip’s and King William’s War, brought a company of militia, and John Russell (College, 1680) went as a surgeon.[31]

According to historian Samuel Adams Drake, the decision to return to Port Royal was unwise, but “… had the support of the people.”[32] On the way to Port Royal, Wainwright found himself saddled with military command when Col Marsh resigned because of poor health and “a broken spirit.”[33] The resignation of Marsh was just the tip of the iceberg. While Wainwright was excited to return to Port Royal and recover his reputation, most of his men were not. They wondered why the officers appointed over them had not just taken the port on the first try. Now, they lacked confidence in their officers to direct a successful second attack and their fighting spirit was almost non-existent.[34]

Young William Dudley also joined the expedition after being appointed by his father as the Secretary of War. It is because of Dudley and his penetrating descriptions that we know of the dissension and low morale in New England ranks.”[35]

At Port Royal, Wainwright lacked the perspective and judgement of an experienced commander. He failed to properly evaluate and assess changes in the garrison's strength. Expecting the French to behave as they had on the first attempt to take Port Royal, he made the mistake of landing his men on August 10, within range of the muskets and cannons of the fort.

The English militiamen took withering fire and quickly abandoned the position. Wainwright then landed his supplies and men at another location, but the French and their Wabanaki allies surrounded the location, the supplies, and his men (many of them sick). Wainwright had reached a low point of his own when he wrote, “The French have reduced us to the same state which we reduced them, at our last being at Port Royal.”[36]

Not willing to accept the embarrassment of defeat, Wainwright withdrew his forces to his ships, reorganized his forces, and attempted once again to take the fort on August 20. The fighting exhausted both sides. The French returned to their fort and the Colonial Militias returned to their ships.

The second attempt on Port Royal had failed. Sixteen colonists died, and many were wounded, not to mention the hundreds who had fallen ill. The French had won a major victory, with only three deaths of their own.[37]

The citizens of New England vilified Wainwright and other leaders of the expedition and labeled them as cowards. Anonymous letters threatened to hang them for their failure.[38] The two failures at Port Royal were a severe blow to Dudley’s reputation and once again caused speculation about his allegiance. As attacks continued on the frontier, his credibility sank still further.

Even so, and to his credit, the Harvard graduate did not point fingers at the questionable performance of the inexperienced military officers on the expedition. Instead, he learned an important lesson. He could not give into impatience, no matter how dissatisfied his fellow New Englanders became. He would need help from Mother England if the colonials were going to get the upper hand on the strongholds at Port Royal and Quebec. He wrote to the Board of Trade in mid-October 1707, asking again for men and ships from England to “remove this troublesome neighbor.”[39]

DUDLEY AND HARVARD COLLEGE

It was during this same time Dudley took time to address an issue at Harvard College that had long languished. Congregational Church minister Increase Mather had been an absentee Harvard College President, living in Boston and England instead of at Cambridge. During Mather’s time as President, the College had declined in the eyes of many New Englanders. After King William’s War, the hold of the Puritan Oligarchy on Harvard College had ended and the Harvard Corporation ousted Mather for refusing to return to Cambridge to live permanently.

With Mather gone, the Vice-President of the College, Rev. Samuel Willard, began superintending the College in September 1701. Willard was married to Governor Dudley’s sister, and with him at the helm, there was no need for change. [40] Dudley was confident of quality leadership, but another issue troubled him. The school had gone without a charter for nearly two decades. In 1864, the Crown revoked the College charter when it revoked the colonial charter. Thought England had since established a new provincial charter, Harvard’s still languished. This was a problem that Dudley wanted to solve.

Furthermore, Joseph Dudley’s father, Thomas Dudley, had helped to establish “the college at Cambridge.” In 1632, he used his own funds to build a palisade enclosing 1,000 acres around Cambridge (called Newtown until 1638). In 1637, Thomas Dudley was on a committee “to take order for a new college at Newtown.”[41] The College received a charter in 1642, with a second charter drafted in 1650. By then, Thomas Dudley was governor and signed the 1650 Harvard College charter into law.

Thomas Dudley died in 1653 and did not have to bear the humiliation of seeing the charter revoked and not replaced. Perhaps during Joseph’s years as President of the Council of New England, and then Chief Magistrate, he believed the Crown would honorably act to replace the charter his father had worked so hard to create. But after a quarter century, failure to create a new charter had become an affront to his family’s honor.

Joseph had a dilemma. He acknowledged that his allegiance to his father was strictly familial, but his allegiance to the Crown, on the other hand, was solemn and binding. Acting contrary to the Crown could lead to recall and punishment.

After taking all these things into account, Dudley revived the College charter by allowing the provincial legislature to vote on it. His decision was a calculated risk, and assumed that since the Crown had not acted on the charter in twenty-four years, reestablishing the 1650 charter without the consent of the British sovereign would most likely go unnoticed (or at least be viewed by the Crown as inconsequential). He was right. The Crown took no action against him, allowing him to reestablish a vital portion of his father’s legacy.[42]

The reinstatement of the 1650 charter was popular, garnering almost universal approval from the colonials. Dudley’s support of the 1650 charter won him much support from those who had previously doubted his allegiances. They saw he could act in the interest of New England independent of the Crown.

History has confirmed his bold action. The State Constitution in 1780 adopted and incorporated the 1650 Harvard charter, and judicial decisions and legislative activities have since uniformly supported its legitimacy.[43]

Historian Josiah Quincy paid tribute to Joseph Dudley as one of “those generous and public-spirited individuals who, in times of political convulsion, amid poverty and embarrassment, by the protection and aid they extended, gave a vigor and expansion to [Harvard College], which rendered it, in the coming age, an object of pride and patronage to the people and legislature of Massachusetts.”[44]

JOHN LEVERETT: HARVARD’S PRESIDENT AND MILITARY VETERAN

Another of Dudley’s actions in the interest of the colonials was to install John Leverett (College, 1680), as the seventh President of Harvard College on January 14, 1708. For nearly all of Dudley’s governorship, Harvard’s chief superintending officer was Vice President Samuel Willard (1701-1707), Dudley’s brother-in-law. Illness, however, forced the steadfast Willard to resign in August 1707 and he died later in the fall.[45]

An important result of reinstating the charter of 1650 was to reduce the number of Harvard Corporation members from seventeen to seven. John Leverett, who had opposed Mather’s proposed charter requiring a faculty loyalty oath to the Puritan interpretation of scripture, was President and one of the seven.[46]

Governor Dudley, by reducing the number of corporation members to seven, removed the influence of Puritan oligarchy led by Increase and Cotton Mather. These two men had assumed one of them would be the new president. Now, neither was the president nor a member of the corporation. They decried what Dudley had done to them as “an open breach upon all the laws of decency, honor, justice, and Christianity.” Dudley had made enemies of the Mathers and their followers, but had made friends of a majority of New England.[47]

By supporting John Leverett, Dudley had placed the first veteran of war in the Harvard Presidency. Besides being a combat veteran of two expeditions against Port Royal, Leverett had taught during the Mather administration (1685-1697). When Mather sailed for England in 1688, Leverett had assumed responsibility for the management of Harvard is affairs.

Leverett was a “statesman, lawyer, judge,” and “religious liberal.” In the opinion of Harvard graduate and historian Samuel Eliot Morison (College, 1908, Ph.D., 1912), Leverett was “the greatest of all the seventeenth-century Harvard graduates.”[48]

The installation of John Leverett (1662-1724) in January 1708 marked the end of over 35 years of institutional instability. According to the online Harvard history of its presidency, Leverett was not only Harvard’s first military veteran president, but became its “first secular president.” It says, “With his extensive and varied background in public life, he loomed large, both in and beyond the Yard.” The history also states that, “Leverett’s major accomplishment as Harvard College president was to help transform Harvard from a divinity school to a more secular institution.” Leverett’s goal, the history states, “was to combine reason and God and to show faith by devotion and purity in living.”[49]

Under Leverett’s secular direction, endowments increased, as did philanthropy. For example, Thomas Hollis, a Baptist merchant from London, provided books and funds so poor students could attend. He also provided a large endowment, creating a chair for a professor of divinity.[50]

HAVERHILL – 1708

With Harvard in excellent hands, Dudley turned his attention to the New England frontier, where in August 1708, the French had mounted a devastating raid on Haverhill, Massachusetts that killed one of Harvard’s own.

The town had grown complacent because of a lack of hostile activity on the frontier for months and had posted no guards. The first house attacked was that of Reverend Benjamin Rolfe (College, 1664). When he heard the attackers enter the village, he ran to his front door and kept them from entering. Frustrated, the attackers fired through the door, striking Rolfe in the elbow. Rolfe turned and ran out the back door. The attackers caught up to him and, not wanting to waste bullets and powder, killed him with their tomahawks. [51]

Rolfe’s wife and baby hid in a closet. When the attackers found them, they killed them with their tomahawks. The raiders search the rest of the house, including the cellar where an enslaved woman named Hagar had hidden the rest of the family and herself under a chest and overturned baskets. The attackers tipped barrels and knocked down shelves just feet away, but didn’t find Hagar and her words. A shout from the top of the stairs saved them, calling the attackers to depart and terrorize another half-dozen homesteads.[52]

As is often the case amid terror, a hero arises. Here, a man named Davis snuck behind Rolfe’s barn and banged on it with a log. He shouted “fictitious commands and called for his imaginary forces to move forward as he continued to strike the building.” His voice rang out across the square. “Come on! We have them!” The French stopped their attack and retreated, but not before killing several dozen, taking a dozen prisoners, and burning down portions of town.[53]

HARVARD GOES BACK TO PORT ROYAL – 1710

Dudley began planning to strike back. In 1709, he sent John Leverett to negotiate with Governor John Lovelace of New York urging military cooperation on the frontier. The resulting campaign on the New York frontier was dismal. With lack of success in 1709, Dudley once again pleaded with England for support.[54]

In 1710, England finally sent help - leadership, soldiers, and firepower. English politician and Lieutenant General Francis Nicholson led a battalion of regulars, two regiments of Massachusetts militia, a company of artillery, and a company of Native American scouts on an expedition against Port Royal. Three of the militia officers were Harvard graduates. Lt Col John Ballantine (College, 1694) served as second in command of Sir Charles Hobby’s 1st Massachusetts Regiment. Several Harvard graduates served in Col William Tailer’s 2nd Massachusetts Regiment. Edmund Goffe (College, 1690) was Lt Col, William Dudley (College, 1704) was Major, and John Whiting (College, 1700) was chaplain. Rev. Thomas Buckingham (College, 1690) and Christopher Christophers (College, 1702) were part of the Connecticut regiment as chaplain and commissary, respectively.[55]

Before following these men ashore at Port Royal, it is valuable to pause for background on a few of these men. John Ballantine was one of Harvard’s most dedicated military men. He became Second Sergeant of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company in 1700, then Ensign (1706), then lieutenant (1708), and finally, captain of that company. He was a merchant and leader in the Boston community. In 1708, he was on a committee of thirty-one to create a “Charter of Incorporation for the better government of [Boston].”[56]

Upon graduation from Harvard, Edmund Goffe entered public life doing odd jobs like constable and surveyor. In the 1710 expedition against Port-Royal, he “scarcely distinguished himself” and afterward was convicted of using his position to defraud the colony by collecting the wages of his personal servant who never served on the expedition. The conviction was later reversed.[57] In 1711, Goffe took part in Sir Hovenden Walker’s failed expedition to Quebec. [58]

John Whiting was minister at Concord for 26 years. He was a good pastor and his congregation loved him. He, however, became addicted to alcohol after the death of his first wife in 1731. On many a Sunday morning, the schoolmaster, Dr. Timothy Minot, a Harvard graduate (College, 1718) would preach the sermon because Whiting was “under the weather.” Ultimately, when Rev. Whiting attempted to walk to the pulpit, but could not because of inebriation, his congregation dismissed him.[59]

During the attack on Port Royal, Colonel Tailor’s regiment, including Lt Col Goffe, Maj Dudley, and Chaplain Whiting, landed the on the north shore as Colonel Walton’s militia regiment accompanied them. The rest of Nicholson’s army landed on the south shore.

As the fort’s cannons blasted away at the advancing English columns, projectiles ripped through the forest canopy above Goffe, Dudley, and Whiting.[60] The English advance guard pushed forward with grapeshot and bullets, making casualties of about six men. They pushed the French pickets back and entrenched about 400 yards from the fort.[61]

Nicholson, a master of operational employment and logistics, ordered the bomb ship Starr forward to begin a mortar attack. While the mortars had little impact on the fort or its inhabitants, they had the intended effect of pulling the fort’s cannons into a dual with the bomb ship. Meanwhile, Nicholson landed his siege guns easily without being shelled by the fort’s preoccupied cannons.[62]

Nicholson took advantage of fog the next morning to land his supplies, and by October 12, unleashed the three batteries he had placed only a few hundred yards from the fort. Cannonballs struck the fort, dirt and stones exploded, and the mortar attack from the Starr resumed.[63]

The bombardment placed the fort in a hopeless situation. As a professional military officer, Nicholson wanted only to achieve the Crown’s objective - replace French control of Port Royal with British control, and nothing more. Having placed his proverbial chess pieces perfectly, and having achieved checkmate, he halted the attack and sent Colonel Tailor forward under a flag of truce, calling for surrender. The French commander capitulated and Nicholson gave the “garrison full honors of war and transport back to France as a salute to their gallant defense.” Nicholson offered local citizens an oath of allegiance to Queen Anne. If they took the oath, they could keep their land and possessions.[64]

Nicholson achieved his objectives and had no compulsion to humiliate the French commander who was “outnumbered ten to one in a fort that was falling down around him, short of food and powder, and surrounded by a garrison that might desert on a moment’s notice…”[65] British casualties amounted to thirty killed or wounded. Nicholson renamed the port Annapolis Royal and sent out messengers with news of the British victory.[66]

PEACE

After Port Royal, the British attempted to capture Quebec in 1711. Young William Dudley was part of the expedition as lieutenant-colonel, but the venture led by Sir Hovenden Walker was ill-fated when much of his fleet became shipwrecked near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River.

The need for large expeditions faded as the French showed signs of running out of men and resources to fight the war and their allies, the Wabanaki tribe, lost the will to fight. Dudley dictated the terms of a treaty that required the Wabanaki to confess their violation of the treaties of 1693, 1699, 1702, and 1703. They became British subjects with all the trade regulations that accompanied that status. For their part, the English agreed to remain west of the Kennebec River.[67]

In Europe, King Louis XIV of France drew back as well. His armies were exhausted and his treasury empty. With the end of the war, France ceded Newfoundland to Great Britain, with certain fishing rights off the coast remaining to the French. Annapolis Royal became British along with all of Acadia (Nova Scotia). France returned Hudson Bay back to the British along with 200,000 pounds to reimburse losses to the Hudson Bay company.[68]

France lost the principal ports of Placentia and Annapolis Royal. England and New England suddenly had new trade opportunities and reduced the threat previously posed by French privateers to New England fishers.[69]

WILLIAM DUDLEY

By 1713, William Dudley (now 28) was colonel and commander of the 1st regiment in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. With Queen Anne’s War at its end, William was part of the peace conference, resulting in Abenakis people of the northeast signing articles of submission on 13 July 1713. William Dudley later took part in peace conferences with native nations or confederations in 1717, 1720, 1722, and after the Indian war of 1722–25. Early in 1725, Lieutenant Governor William Dummer sent Dudley and Samuel Thaxter to Montreal to seek an end to French help to the Native American tribes in Dummer’s War and to get a release of captives. The French formally denied giving the Indians military aid, but released 26 captives.

William Dudley held various public offices during his life. In 1713, he became a justice of the peace and was a sheriff about the same time. He served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1718 to 1729 and was speaker of the house (1724–29). From 1729 until his death, he sat on the Massachusetts Council.

Over time, Dudley became known as a “gentleman woodsman” because of his knowledge of the back country. As a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1718 to 1729 (where he was speaker of the house from 1724 to 1729), he “served on every important boundary commission dealing with Massachusetts’ disputes with her neighbors and on many committees concerned with military and Indian affairs.” He became “the most knowledgeable legislator on land value and other provincial matters.”[70]

HARVARD SUPPORT AND PARTICIPATION

Harvard graduates played a major role in Queen Anne’s War, with the principal participants being Governor Joseph Dudley, John Leverett, William Dudley, Francis Wainwright, and John Williams. Support for the war among Harvard faculty, students, and alumni was strong, with limited descension coming from the displaced Puritan elite, led by Increase and Cotton Mather (both Harvard graduates). Their dissention was not reflective of staunch opposition to fighting the French and their allies, but expressed the resentment they felt for men who had wrested control of Harvard College from them – Dudley and Leverett.

As in King Philip’s and King William’s Wars, Harvard graduates played a major role in creating and executing military and political strategy. Joseph Dudley proved to be masterful in holding New England together to win “the long war” and in the end take territory the French had previously used to terrorize British seagoing movements on the Atlantic Coast. Leverett led both in the field and in “the yard.” Young William Dudley took part in many an expeditions and negotiations to become one of the most experienced woodsmen and statesmen in the colonies by the young age of twenty-eight.

[1] See Article 2: HARVARD AND KING PHILIP’S WAR (1675-1678), Harvard Veterans Alumni Organization

[2] Viola Florence Barnes, The Dominion of New England: A Study in British Colonial Policy (Yale University Press: New Haven, 1923), 6, 10-18.

[3] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge University, Vol. 2, (Charles William Sever: Cambridge, 1881) 428-431.

[4] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University in Cambridge University, Vol. 2, (Charles William Sever: Cambridge, 1881) 427-429.

[5] Everett Kimball, The Public Life of Joseph Dudley: A Study of the Colonial Policy of the Stuarts in New England, 1660-1715, (Longmans, Green & Co.: New York & London, 1911), 76-82.

[6] Kimball, The Public Life of Joseph Dudley, 76-82.

[7] Michael G. Laramie, Queen Anne's War: The Second Contest for North America, 1702–1713 (Westholme: Yardley, 2021), 49.

[8] Laramie, 50.

[9] Laramie, 50-69.

[10] Laramie, 69.

[11] Laramie, 74; Evan Haefeli and Kevin Sweeney, Captors and Captives: The 1704 French and Indian Raid on Deerfield (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 100, 111; Colin Gordon Calloway, After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997), 31.

[12] Michael G. Laramie, Queen Anne's War, 75,76; John Williams, The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion; or, The Captivity and Deliverance of Rev. John Williams of Deerfield (Springfield, MA: H.R. Huntting Co, 1908), 9-11.

[13] Drake, Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1897), 182-183.

[14] Drake, Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1897), 183

[15] Haefeli and Sweeney, Captors and Captives, 128.

[16] Richard Melvoin, New England Outpost: War and Society in Colonial Deerfield (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989), 481; Haefeli and Sweeney, Captors and Captives, 130; John Demos, The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America (New York: Knopf, 1994), 38–39.

[17] Lyman S. Hayes, History of the Town of Rockingham, Vermont: Including the Villages of Bellows Falls, Saxtons River, Rockingham, Cambridgeport and Bartonsville, 1753-1907, with Family Genealogies (Bellows Falls, VT, 1907) Retrieved 11 Feb 2022 at https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=ULmlDG8KLjYC&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&authuser=0&hl=en&pg=GBS

[18] Samuel Eliot Morison “Harvard in the Colonial Wars, 1675-1748,” The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine, Vol. XXVI, September, 1917, 565; Laramie, Queen Anne's War, 80; Williams, Redeemed Captive, 13-35.

[19] Haefeli and Sweeney, Captors and Captives, 190, 191; Melvoin, New England Outpost, 229.

[20] Laramie, Queen Anne's War, 83.

[21] Andrew Hill Clark. Acadia, the Geography of Early Nova Scotia to 1760 (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968), 220.

[22] Laramie, Queen Anne's War, 90.

[23] Morison “Harvard in the Colonial Wars,” 566.

[24] Drake, Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1897), 183.

[25] Morison “Harvard in the Colonial Wars,” 566; http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dudley_william_3E.html Dictionary or Canadian Biography.

[26] Laramie, Queen Anne's War, 129,130; http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dudley_william_3E.html

[27] Laramie,132.

[28] Laramie, 218-219; Francis Nicholson, Journal of an Expedition Performed by the Forces of Our Soveraign Lady Anne, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France and Ireland, Queen, Defender of the Faith, &c: Under the Command of the Honourable Francis Nicholson, General and Commander in Chief, in the year 1710 for the Reduction of Port-Royal in Nova Scotia, or any Other Place in Those Parts in America, then in Possession of the French. London: self-published, 1711), 79-89.

[29] Morison “Harvard in the Colonial Wars,” 566; John Farmer, A Genealogical Register of the First Settlers of New England. Lancaster (Mass.: Carter, Andrews & Co, 1829), 299; Joseph B. Felt, History of Ipswich, Essex, and Hamilton (C. Bolton: Cambridge, 1834), 18, 168, 173; Thomas Franklin Waters, Ipswich in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Ipswich: The Ipswich Historical Society, 1917), 54.

[30] http://www.ahac.us.com. According to Harvard Library, HOLLIS for Archival Discovery, “In 1707, as a lieutenant in the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, Leverett organized and commanded a company of volunteers for an aborted expedition against the French at Port Royal in Nova Scotia, Collection: Papers of John Leverett, 1652-1730 | HOLLIS for (harvard.edu), The collection, however, does not contain a source document validating this claim.

[31] Drake, 234; Morison, 566.

[32] Drake 234.

[33] Laramie,227.

[34] Morison, 566.

[35] http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dudley_william_3E.html

[36] Laramie, 228.

[37] Laramie, 229.

[38] John Langdon Sibley, Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University. Vol. 3 (Cambridge: C. W. Sever, 1885), 354-55.

[39] Laramie, 218-219.

[40] Josiah Quincy, The History of Harvard University (John Owen: Cambridge, 1840), 145, 148.

[41] Augustine Jones, The Life and Work of Thomas Dudley, the Second Governor of Massachusetts (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin, 1900), 243.

[42] Quincy, 160; Morison, 195. The Dudley House at Harvard has been torn down. It is now only an administrative unit located in Lehman Hall. There once was a Dudley Gate at Harvard, with an inscription written by his daughter Anne. The gate was removed in the 1940s when the Lamont Library was built. The inscription remains in Dudley Garden, behind Lamont Library. Harvard Library Bulletin, Volume 29 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1981), 365; Yael M. Saiger, “Closing a Gate, Creating a Space,” The Harvard Crimson, 5 May 2017; Rose Lincoln “Hidden Spaces: Secret Garden,” Harvard Gazette, 2 September 2014.

[43] Quincy, 161.

[44] Quincy, 162.

[45] Quincy, 201.

[46] Quincy, 201. Nehemiah Hobart, William Brattle, Ebenezer Pemberton, Henry Flynt, and Jonathan Remington were Fellows. Thomas Brattle was Treasurer.

[47] Quincy, 201-202.

[48] Morison, 566; https://web.archive.org/web/20100612033858/http://www.president.harvard.edu/history/07_leverett.php

[49] https://web.archive.org/web/20100612033858/http://www.president.harvard.edu/history/07_leverett.php

[50] https://web.archive.org/web/20100612033858/http://www.president.harvard.edu/history/07_leverett.php

[51] Drake, 244-245; George Wingate Chase, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, from Its First Settlement, in 1640, to the Year 1860 (Haverhill: G.W. Chase, 1861), 218 – 220.

[52] Drake, 244-245; George Wingate Chase, The History of Haverhill, Massachusetts, from Its First Settlement, in 1640, to the Year 1860 (Haverhill: G.W. Chase, 1861), 218 – 220.

[53] Laramie 334-36; Chase, The History of Haverhill, 223.

[54] Laramie, 276.

[55] Morison, 567

[56] Drake, Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1897), 183.

[57] http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/goffe_edmund_2E.html; https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Genealogical_Magazine/BBAzAQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Col.+Edmund+Goffe&pg=PA366&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=Col.%20Edmund%20Goffe&f=false

[58] http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/goffe_edmund_2E.html; Letter from William Dummer to Edmund Goffe, 27 July 1724. Four years later, he was a commissioner negotiating with the Cape Sable Indians after they seized twenty-seven New England fishing vessels. He represented Cambridge in the Massachusetts General Court in 1716, 1720, and 1721, where he served on a committee dealing with Indian affairs.

Later, during Dummer’s War (1722-1725) against the Abenaki Indians on Massachusetts’ frontier, Goffe commanded forces along the western frontier between Brookfield and Salisbury. He was a competent military officer who made sure the militias in the towns were “effective and well-armed,” and maintained scouting parties in the wilderness between the Connecticut and Merrimack Rivers. While his primary task was to protect the towns, the Governor also empowered him to assemble forces to strike out at the enemy to repel them.

After three years as commander of the frontier, someone again accused Goffe of fraud. He returned to considerable financial difficulties and became “a poor bankrupt lost wretch.” The biographer C. K. Shipton later wrote that “Col. Goffe’s services . . . were not so notable for fighting as for a system of graft which he and some of his fellow officers developed.”

[59] https://www.firstparish.org/ministers/. When a group of about 20 people broke away from the Concord Church, they asked Rev. Whiting to be their leader as they conducted weekly services in the Black Horse Tavern, vacant, on a Sunday morning. Whiting’s church became known as “the Black Horse Church.” His drinking aside, contemporaries said that Whiting “…never detracted from the character of any man and was a universal lover of mankind.”

[60] Francis Nicholson, Journal of an Expedition, 64-67; Drake, Samuel Adams Drake, The Border Wars of New England (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1897), 259-260.

[61] Laramie, 279.

[62] Laramie, 280.

[63] Francis Nicholson, Journal of an Expedition, 67-79.

[64] Nicholson, 79-89; Laramie, 280.

[65] Laramie, 281.

[66] Laramie, 281, 290.

[67] Laramie, 306.

[68] John Almon, A Complete Collection of Treaties from 1688 to 1771 (University of Michigan, 1772), 136-141, 171-176.

[69] Laramie, 308.